The history of Australia is similar to the Americas with European settlers displacing the native peoples by means of force. As time went by, the European invaders have grown more respectful both in Australia and the Americas. This exhibition explores the Aboriginal peoples art and it’s connection with the true nature and experience of the landscape of Australia. The “more appropriate” terms describing the native people of Australia stress the humanity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. “Aboriginal” which in Latin means “from the beginning” and other such European words are used because there is no Aboriginal word that refers to all Aboriginal people in Australia. When we entered this room we immediately felt the spiritually and beauty of the art. The baskets glowed in their own quiet way, the fishing baskets enhanced the room and the paintings completed the picture in a truly Aboriginal people’s way.

These baskets represent an enormous amount of work. First the leaves of the Pandanus screw are taken, usually young leaves so as to not damage the plant. The leaves are scraped, in the past with a shell but probably today with a knife. Next, the leaves are cut into very thin strips and possibly dyed with vegetable dyes. The resulting strips can be broken down as string or retained as strips to be woven into these lovely Pandanus palm coil baskets. A dillybag or dilly bag is a traditional Australian Aboriginal bag, generally woven from the fibres of plant species of the Pandanus genus. It is used for a variety of food transportation and preparation purposes. Dilly comes from the Jagera word dili, which refers to both the bag and the plants from which it is made. The dilly bag, otherwise known as yakou, yibali or but but bag, is a bag worn around the neck to hold food like berries, meat, fish and roots.

Pandanus is a large genus of about 600 trees and shrubs from Australia, Asia and Africa. Most plants in this species have broad and dense leaves. These deciduous plants produce male and female flowers on separate plants. Fruits resemble the fruit of pineapple plant. Pandanus are a good choice for planting outdoors for their handsome foliage. Pandanus spiralis is native to northern Australia. It is commonly called common screwpine, iidool, pandanus palm, screw pine, screw palm or spring pandanus. It is neither a true palm, nor a pine. Pandanus spiralis is a shrub or small tree up to 10 metres in height. It has long, spiny leaves organised in a spiral arrangement. The young leaves of P. spiralis can be cut into thin strips then used to weave neckbands and armbands. The fibre of the leaves can be used as string for dillybags. Other uses include baskets, mats, and shelters. The meanings associated with the word “flax” have changed over time, especially in New Zealand and Australia. Several entirely different plant species are now commonly referred to as flax; including Linen flax (Linum usitatissimum), Native New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax and Phormium cookianum) known by Māori as harakeke and wharariki, Pandanus, a genus of 600+ species, found in Australia and the Pacific Islands, but not in New Zealand and a wide variety of plants that can be woven in flat strips. Although the fibre of linen flax and New Zealand flax is similar, the plants are very different. Linen flax is a fine-leaved shrub and its fibre is taken from its stems, whereas New Zealand flax grows long, tough leaves from the base of the plant, and its leaves can be peeled for fiber or cut into strips. Screw Pine (Pandanus fascicularis) is a species of Pandanus native to southern Asia, from southern India east to Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands south of Japan, and south to Australia. It is a shrub with fragrant flowers. They are used to extract perfume, aromatic oil (kevda oil) and fragrant distillations (otto) called “keorra-ka-arak”.

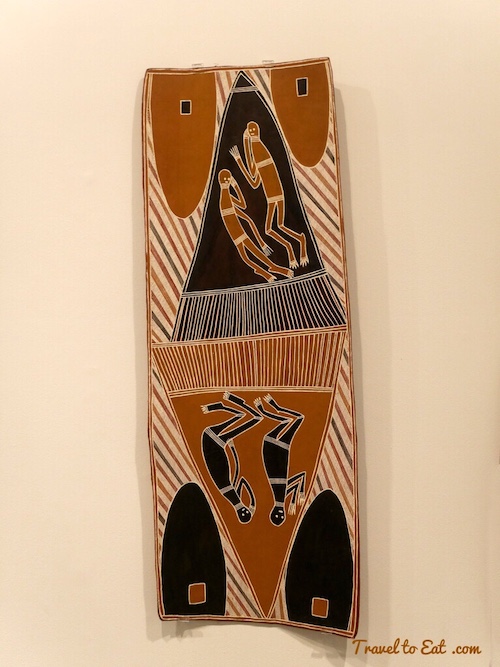

These two paintings are actually landscape paintings/topographic maps, look closely and you can see valleys, elevations and cliffs. Australians have developed and are bound by highly complex belief systems that interconnect the land, spirituality, law, social life and care of the environment. The terms Dreamtime, Dreaming and Songlines are regularly used and interchanged to describe these important elements of Aboriginal cultures. Many of the Dreaming stories are presented as elaborate song cycles (Songlines) that relate to a specific place, group and individual. They provide a map recording details of the landscape and express the relationship between the land, sea and the people. Songlines are about singing where you’ve been or creating a map with words. The literal concept of Songlines is to “sing the trail”, to “sing the place”, to recreate and remember the physical landscape in song. And, it should be noted, this doesn’t just apply to a literal landscape. Since few of us rely on a literal landscape for our sustenance anymore this concept can be extended to any figurative landscape. We all yearn for a sense of place and this is one way to achieve it. Songlines in Australia can extend thousands of miles. Aborigines can unerringly find their way across terrain unknown to them simply by knowing the land’s song–the songline. Since a songline can span the lands of several different language groups, different parts of the song are said to be in those different languages. Languages are not a barrier because the melodic contour of the song describes the nature of the land over which the song passes. The rhythm is what is crucial to understanding the song. Listening to the song of the land is the same as walking on this songline and observing the land. Here we see amazing interpretations of the Songline into paintings of landscapes where the view is interpreted by lines rather than a painting of trees, meadows, mountains and buildings.

“Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s work is distinguished by its vitality, boldness and innovation. She was from the remote community of Utopia, north east of Alice Springs, and like other celebrated Aboriginal artists, she began painting late in life. Not only was her output prodigious, she developed five consecutive styles in the eight years before her death. These works by Kngwarreye are drawn from traditional body painting designs used in women’s ceremonies. The subject of Kngwarreye’s art was her traditional country and ceremony, centred around “Awelye”, her Dreaming. “Awelye” is the word used to describe the actual painted designs on the body, but it also has a broader meaning, referring to the content of a ceremony and the associated body of knowledge. Thus these simple lines are much more than stylised body paint; there are many other references, including the lines left in the sand and cuts made in the upper arm as a sign of mourning.” Here we see a lovely interpretation of the Songline into the parts and shapes of the female body. I am reminded of the poem by Charles Baudelaire, truly an erotic song/voyage in the spirit of the Songline:

Parfum exotique

Quand, les deux yeux fermés, en un soir chaud d’automne,

Je respire l’odeur de ton sein chaleureux,

Je vois se dérouler des rivages heureux

Qu’éblouissent les feux d’un soleil monotone;

Une île paresseuse où la nature donne

Des arbres singuliers et des fruits savoureux;

Des hommes dont le corps est mince et vigoureux,

Et des femmes dont l’oeil par sa franchise étonne.

Guidé par ton odeur vers de charmants climats,

Je vois un port rempli de voiles et de mâts

Encor tout fatigués par la vague marine,

Pendant que le parfum des verts tamariniers,

Qui circule dans l’air et m’enfle la narine,

Se mêle dans mon âme au chant des mariniers.

— Charles Baudelaire

Exotic Perfume

On autumn nights, eyes closed, when, sensuous,

I breathe the scent of your warm breasts, my sight

Is peopled by far shores, happy and bright,

Under a sun, warm and monotonous.

A lazy isle which nature, generous,

Stocks with weird trees and fruits of strange delight,

Men with lithe bodies, powerful but slight,

Women whose candid eyes flash luminous.

Urged by your scent to such charmed lands at last,

I see a port with many a sail and mast

Still weary from the ocean’s frenzied roll,

While the green tamarinds exhale their savor

To please my nostrils with a dulcet flavor,

Mingled with sailor chanteys in my soul.

— Jacques LeClercq, Flowers of Evil (Mt Vernon, NY: Peter Pauper Press, 1958)

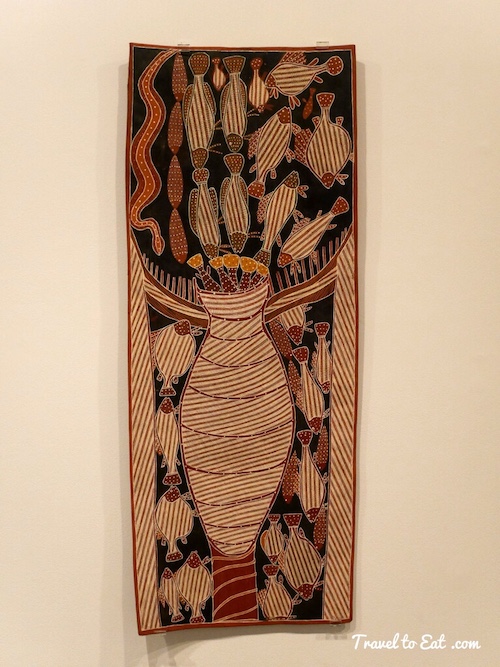

Fiberwork nets, traps, baskets and bags are used extensively for fishing and hunting. In earlier times, fiber objects were crucial for the sustenance of family groups. Looped or twined fiber nets were used to catch kangaroos and emus, as well as ducks, fish and eels. The Maningrida region is known for conical fish traps made by men and now sometimes by women. Traditionally the conical fish traps were used in conjunction with long mats that are used as barriers in creeks to divert fish into the trap. Burarra and Kuninjku people are particularly renowned for making fish traps. Burarra make conical fish traps called jina-bakara, using pandanus (pandanus spiralis). The Kuninjku people traditionally make two sorts of conical fish traps, one called Mandjabu made from milil (Malaisia scandens) a vine and a smaller one called Manyilk Mandjabu made from the grass manyilk (Cyperus javanicus). The milil (large) conical fish trap is bigger and stronger than the manyilk variety and is used in tidal reaches of creeks to catch large fish. The smaller and lighter manyilk trap is used in fresh water flowing creeks to catch small fish and fresh water prawns. Traditionally, only men were involved in the construction of the large fish traps, but small children were used to crawl inside to assist with the inner trap. Traps like these are still used worldwide for crab, lobster and eels and were independently invented across the world as long as 9000 years ago. Not only are they utilitarian but these traps represent an art that combines form and timeless function.

These two bark paintings represent one or two dreamtime stories, from a period in the past when the world was being formed. An uninitiated man or woman is only allowed to paint outside stories, the sort of story that might be told to a child. An initiated man can paint an inside story, which is restricted knowledge. Thus, a painting may be displayed in an exhibition, or put up for sale, but the artist, although having the right to paint the story, does not have the right to tell the story to another person. I have found a dreamtime story that fits with the above bark paintings although it is not necessarily the story associated with these paintings. In the first is a depiction of catching fish with a fiberwork trap and the second shows a man and woman with dilly bags, perhaps the Boodi and Yalima of the following story:

In the Barramundi dreamtime long ago, there were no fish, so the people lived on animals, roots and berries. They were all quite content. That is except Boodi and Yalima; for they wanted to marry. But the tribe insisted that Yalima marry one of the old men, to look after him. Boodi and Yalima decided to run away, and so they did. Now, to go against the Elders of the tribe is breaking the law, and is punishable by death, so soon the men of the tribe began hunting them.They ran on and on, although they became very tired, they had to keep running. Eventually, they came to the edge of the land, where the water began and they knew that to survive, they would have to fight. With the angry tribe descending on them, they quickly gathered wood, and made as many spears as they could. But the tribesman were too many, and soon the spears were all gone. Boodi turned to his beloved Yalima and said, “for us to be together forever, we must go into the water to live.” And so they did.

The material of choice for bark paintings is the bark from Stringybark (Eucalyptus tetradonta). The bark must be free of knots and other blemishes. It is best cut from the tree in the wet season when the sap is rising. Two horizontal slices and a single vertical slice are made into the tree, and the bark is carefully peeled off with the aid of a sharpened tool. Only the inner smooth bark is kept and placed in a fire. After heating in the fire, the bark is flattened under foot and weighted with stones or logs to dry flat. Once dry, it is ready to paint upon. Earth pigments, or ochres, in red, yellow and black are used, also mineral oxides of iron and manganese and white pipeclay, or calcium carbonate. Ochres may be fixed with a binder such as PVA glue, or previously, with the sap or juice of plants such as orchid bulbs. The designs seen on authentic bark paintings are traditional designs that are owned by the artist, or his “skin”, or his clan, and cannot be painted by other artists. In many cases these designs would traditionally be used to paint the body for ceremonies or rituals, and also to decorate logs used in burials ceremonies. The Dreamtime is the period of creation when the world was a featureless void where ancestral spirits in human and other life forms emerged from the earth and the sky creating all living things and the landscape we see today. All Aboriginal people have a common belief in the creation or Dreaming, which is a time when the ancestral beings travelled across the country creating the natural world and making laws and customs for Aboriginal people to live by. The Dreaming ancestors take the form of humans, animals or natural features in the landscape. The term “Dreaming” is directly based on the term Altjira (Alchera), the name of a spirit or entity in the mythology of the Aranda. Related entities are known as Mura-mura by the Dieri, and as Tjukurpa in Pitjantjatjara.

The category “Aboriginal Australians” was coined by the British after they began colonising Australia in 1788, to refer collectively to all people they found already inhabiting the continent, and later to the descendants of any of those people. Before 1788, it is estimated there were approximately 200-250 different languages spoken by Aboriginal people living throughout Australia. This translates to an equal number of tribes or peoples in Australia. The Australian Aboriginal Flag was designed in 1971 by Aboriginal artist Harold Thomas, who is descended from the Luritja people of Central Australia and holds intellectual property rights to the flag’s design. It is often flown together with the national flag and with the Torres Strait Islander Flag, which is also an official flag of Australia:

- Black: Represents the Aboriginal people of Australia

- Red: Represents the red earth, the red ochre and a spiritual relation to the land

- Yellow: Represents the Sun, the giver of life and protector

There are a number of other names from Australian Aboriginal languages commonly used to identify groups based on geography, including But not complete:

- Anangu in northern South Australia, and neighbouring parts of Western Australia and Northern Territory

- Bama in north-east Queensland

- Koori (or Koorie or Goori or Goorie) in New South Wales and Victoria

- Murri in southern Queensland

- Noongar in southern Western Australia

- Nunga in southern South Australia

- Palawah (or Pallawah) in Tasmania.

In a genetic study in 2011, researchers found evidence, in DNA samples taken from strands of Aboriginal people’s hair, that the ancestors of the Aboriginal population split off from the ancestors of the European and Asian populations between 62,000 and 75,000 years ago—roughly 24,000 years before the European and Asian populations split off from each other. Aboriginal people have been living continuously in Australia for more than 50,000 years.

[mappress mapid=”84″]

References:

Museum of Contempory Art: http://www.mca.com.au/

Koori History: http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Aboriginal_Australians.aspx

2009 Exhibition Catalog: http://www.unisa.edu.au/Global/Samstag/Exhibitions/2009/Documents/SMASkincatalogue.pdf

Racial Slurs of Aboriginal Australians: http://www.rsdb.org/race/australian_aboriginals

Indigenous People of Australia: http://www.flinders.edu.au/equal-opportunity_files/documents/cdip/folio_5.pdf

Pandana: http://www.thelovelyplants.com/category/trees/page/8/

Plaiting Techniques: http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-MacToke-t1-body-d1-d10-d3.html

Flax: http://www.alibrown.co.nz/history-of-new-zealand-flax.html

Durrmu Arts: http://www.durrmu.com.au/art-works/weaving

How to Coil a Basket: http://www.craftypod.com/2008/04/19/how-to-coil-a-basket/

Dreamtime, Songlines and Stories: http://www.tourism.australia.com/aboriginal/dreamtime-stories-and-songlines.aspx

Songlines: http://www.navaching.com/hawkeen/sline.html

Pandanus Fish Traps: http://tenpsnt.tripod.com/PhotoList/pandanus_spiralis.htm

9000 Year Old Fish Traps: http://www.abroadintheyard.com/9000-year-old-fishing-traps-found-on-bottom-of-baltic-sea/

Aboriginal People’s Dreamtime Stories: http://www.didjshop.com/stories/