The abandoned Armenian city of Ani in north-east Turkey is a reminder of the Armenian history of this region. Visitors who pass through Ani’s city walls are greeted with a panoramic view of ruins that span three centuries and five empires, including the Bagratid Armenians, Byzantines, Seljuk Turks, Georgians and Ottomans. The ruins of the former mighty capital of Armenian Kingdom Bagratuni lie right on the Turkish-Armenian border. At the time of its greatest glory it competed in its importance to the largest towns in the Middle East. It was protected by canyons of rivers on three sides and on the fourth by powerful walls. Between 961 and 1045, it was the capital of the Bagratid Armenian kingdom that covered much of present-day Armenia and eastern Turkey. Called the “City of 1001 Churches”, Ani stood on various trade routes and its many religious buildings, palaces, and fortifications were amongst the most technically and artistically advanced structures in the world. At its height, the population of Ani probably was on the order of 100,000. Long ago renowned for its splendor and magnificence, Ani was sacked by the Mongols in 1236 and devastated in a 1319 earthquake, after which it was reduced to a village and gradually abandoned and largely forgotten by the seventeenth century. Ani is a widely recognized cultural, religious, and national heritage symbol for Armenians.

Armenian chroniclers such as Yeghishe and Ghazar Parpetsi first mentioned Ani in the 5th century. They described it as a strong fortress built on a hilltop and a possession of the Armenian Kamsarakan dynasty. In 1064, a large Seljuk army under Alp Arslan attacked Ani. After a siege of 25 days, they captured the city and slaughtered its population. In 1072, the Seljuks sold Ani to the Shaddadids, a Muslim Kurdish dynasty. The Shaddadids generally pursued a conciliatory policy towards the city’s overwhelmingly Armenian and Christian population and actually married several members of the Bagratid nobility. Whenever the Shaddadid governance became too intolerant, however, the population would appeal to the Christian kingdom of Georgia for help. The Georgians captured Ani five times between 1124 and 1209. The first three times, it was recaptured by the Shaddadids. In the year 1199, Georgia's Queen Tamar captured Ani and gave the governorship of the city to the generals Zakare and Ivane. They were succeeded by Zakare's son Shahanshah. Zakare's new dynasty, the Zakarids, considered themselves to be the successors to the Bagratids. Prosperity quickly returned to Ani, its defences were strengthened and many new churches were constructed. The Mongols unsuccessfully besieged Ani in 1226, but in 1236 they captured and sacked the city, massacring large numbers of its population. Today, the small Turkish village of Okacli accompanies the archeology site of Ani and the small Armenian village of Kharkov is on the other side of the Akhurian River.

A line of walls that encircled the entire city defended Ani. The most powerful defences were along the northern side of the city, the only part of the site not protected by rivers or ravines. Here the city was protected by a double line of walls, the much taller inner wall studded by numerous large and closely space semicircular towers. Contemporary chroniclers wrote that King Smbat (977–989) built these walls. Later rulers strengthened Smbat's walls by making them substantially higher and thicker, and by adding more towers. Armenian inscriptions from the 12th and 13th century show that private individuals paid for some of these newer towers. The northern walls had three gateways, known as the Lion Gate, the Kars Gate, and the Dvin Gate (also known as the Chequer-Board Gate because of a panel of red and black stone squares over its entrance). The defenses on the triangular south side were provided by the Akhourian and Tsalkotsajour rivers.

The Akhurian, Akhuriyan, Akhuryan or Akhouryan is a river in the South Caucasus. It originates in Armenia and flows from Lake Arpi, along the border with Turkey, forming part of the geographic border between the two states, until it flows into the Aras River as a left tributary near Bagaran. Several medieval bridges once existed over the Akhurian River. The bridge at Ani may date back to the Bagratuni Dynasty. More likely it dates to the thirteenth century. An inscription found nearby said that building work was done on the approach to the bridge in the early fourteenth century. Only the two ends of the stone bridge remain today; one on either side of the river. The structure originally could be opened and closed via ropes and, when needed, elevated to make it impassable from the road, said Samvel Karapetian, head of the Yerevan branch of the Research on Armenian Architecture non-governmental organization, who wants to rebuild the bridge. Nineteenth-century travelers reported a guardhouse next to the bridge, but this has since disappeared.

The church of St Gregory of Tigran Honents, finished in 1215, is the best-preserved monument at Ani. It was built during the rule of the Zakarids and was commissioned by the wealthy Armenian merchant Tigran Honents. Its plan is of a type called a domed hall. In front of its entrance are the ruins of a narthex and a small chapel that are from a slightly later period. The exterior of the church is spectacularly decorated. Ornate stone carvings of real and imaginary animals fill the spandrels between blind arcade that runs around all four sides of the church. The interior contains an important and unique series of frescoes cycles that depict two main themes. In the eastern third of the church is depicted the Life of Saint Gregory the Illuminator, in the middle third of the church is depicted the Life of Christ. Such extensive fresco cycles are rare features in Armenian architecture, it is believed that these ones were executed by Georgian artists, and the cycle also includes scenes from the life of St. Nino, who converted the Georgians to Christianity. In the narthex and its chapel survive fragmentary frescoes that are more Byzantine in style.

Cick here for the next page

The Cathedral of Ani was completed in 1001 by the architect Trdat in the ruined ancient Armenian capital of Ani, located in what is now the extreme eastern tip of Turkey, on the closed border with modern Armenia. It offers an example of a domed cruciform church within a rectangular plan, though both the dome and the drum supporting it are now missing, having collapsed in an earthquake in 1319. A further earthquake in 1988 caused the collapse of the north-west corner, and weakened all the west side. From 992 to 1058 what is now the Armenian Patriarchy or Catholicosate of the Holy See of Cilicia (full name the Armenian Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia) was relocated to the Arkina district in the suburbs of Ani, where the cathedral stands. In 1001, the leading architect Trdat completed the building of the Catholicosal palace and the Mother Cathedral of Ani. It was begun in 989 by order of King Smbat II and was completed “by order of my husband” under the patronage of the wife of King Gagik I, Queen Katranide. The cathedral was dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, and is one of the architectural masterpieces of Armenia. Following the Seljuk Turkish victories in Western Armenia, Sultan Alp Arslan in 1064 took down the crosses from the cathedral after entering the city and in 1071 it was turned into a mosque.

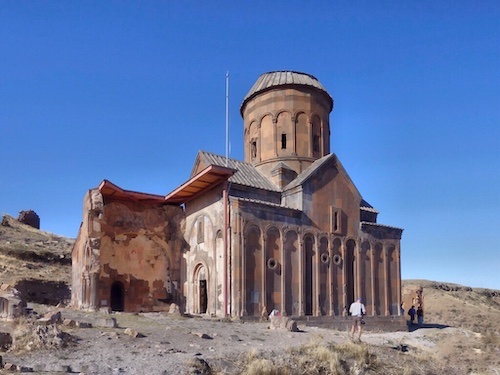

According to it's inscriptions the “Church of the Surp” Amenap'rkitch was built in 1035 to house a piece of the “true cross” by Prince Abulgharib Pahluvani. A Zhamatun (an Armenian hall for gathering and studies) was added in 1193 for the accommodation of the pilgrims and a bell tower was added next to the main entrance. Earthquake damage to the church is reported for the first time in 1131. It's dome was restored in 1342 to following the disastrous earthquake of 1319. When Nikolai Yakovlevich and his team started the first scientific excavations at Ani (1892-1917) the church was still standing but in an unstable condition. In 1912 they restored the restored the walls of the church to prevent a total collapse. Marr's intervention with smaller size masonry in darker colors than the originals can now be easily recognized. Nonetheless the eastern half of the church collapsed completely in 1957. The still standing western half which was badly damaged in the 1988 earthquake and is under the threat of total collapse. In 2010 World Monuments Fund and Ministry of Culture and Tourism signed a memorandum of understanding for the conservation of the Prikitch church. Works began in 2012 with funding from the US ambassadors fine for a cultural preservation, US Department of State and Embassy of the United States, Ankora.

The Mosque of Manuchihr is named after its presumed founder, Manuchihr, the first member of the Shaddadiddynasty that ruled Ani after 1072. The oldest surviving part of the mosque is it's still intact minaret from about 1000 CE. It has the Arabic word Bismillah (“In the name of God”) in Kufic lettering high on its northern face. The prayer hall, half of which survives, dates from a later period (the 12th or 13th century). In 1906 the mosque was partially repaired in order for it to house a public museum containing objects found during Nicholas Marr's excavations. The original purpose of the mosque of Manuchihr is debated on both the Turkish and Armenian sides. Some contend that the building once served as a palace for the Armenian Bagratid dynasty and was only later converted into a mosque. Others argue that the structure was built as a mosque from the ground up, and thus was the first Turkish mosque in Anatolia. From 1906 to 1918, the mosque served as a museum of findings from Ani’s excavation by the Russian archaeologist Nicholas Marr. Regardless of the building’s origins, the mosque’s four elegant windows display spectacular views of the river and the other side of the gorge.

The church of St Gregory of the Abughamrents is a small building probably dating from the late 10th century. It was built as a private chapel for the Pahlavuni family. Their mausoleum, built in 1040 and now reduced to its foundations, was constructed against the northern side of the church. Built sometime in the late 10th Century, the Church of St Gregory of the Abughamrentsis a stoic-looking, 12-sided chapel that has a dome carved with blind arcades, arches that are purely for embellishment instead of leading to a portal. In the early 1900s, a mausoleum was discovered buried under the church’s north side, likely containing the remains of the church’s patron, Prince Grigor Pahlavuni of the Bagratid Armenians, and his kin. Unfortunately, like many of the sites at Ani, the prince’s sepulchre was looted in the 1990s.

Opposite the Church of St Gregory of the Abughamrents are a series of caves dug out of the rock, which some historians speculate may predate Ani. The caves are sometimes described as Ani’s “underground city” and signs point to their use as tombs and churches. In the early 20th Century, some of these caves were still used as dwellings.

Also known as the Gagikashen, this church was constructed between the years 1001 and 1005 and intended to be a recreation of the celebrated cathedral of Zvartnots at Vagharshapat. Nikolai Marr uncovered the foundations of this remarkable building in 1905 and 1906. Before that, all that was visible on the site was a huge earthen mound. The designer of the church was the architect Trdat. The church is known to have collapsed a relatively short time after its construction and houses were later constructed on top of its ruins. Trdat's design closely follows that of Zvartnotz in its size and in its plan (a quatrefoil core surrounded by a circular ambulatory).

At the southern end of Ani is a flat-topped hill once known as Midjnaberd (the Inner Fortress). It has its own defensive walls that date back to the period when the Kamsarakan dynasty ruled Ani (7th century AD). Nicholas Marr excavated the citadel hill in 1908 and 1909. He uncovered the extensive ruins of the palace of the Bagratid kings of Ani that occupied the highest part of the hill. Also inside the citadel are the visible ruins of three churches and several unidentified buildings. One of the churches, the “church of the palace” is the oldest surviving church in Ani, dating from the 6th or 7th century. Marr undertook emergency repairs to this church, but most of it has now collapsed, probably during an earthquake in 1966. I hope you enjoyed this post, please take the time to leave a comment.

[mappress mapid=”175″]

References:

Ghost City of Ani: http://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2014/01/the-ancient-ghost-city-of-ani/100668/

Ani Ghost City: http://www.atlasobscura.com/places/ani-ghost-city

Ani: http://www.gigaplaces.com/en/photoreport-ani-364/

Ani: http://www.peopleofar.com/2014/01/13/ani-city-of-1001-churches-2/

BBC: http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20160309-the-empire-the-world-forgot

Bridge at Ani: http://www.eurasianet.org/node/61347

Cave Dwellings: http://virtualani.org/caves/index.htm

Mosque of Manuchihr: http://virtualani.org/minuchihrmosque/index.htm

Wikitravel: http://wikitravel.org/en/Ani

Drawing of Ani: http://virtualani.org/maps/reconstruction.htm