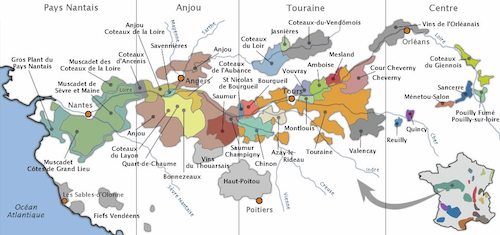

The architectural heritage in the Loire Valley’s historic towns is notable, especially its châteaux, such as the Château d’Amboise, Château de Chambord, Château de Chinon, Château du Rivau, Château d’Ussé, Château de Villandry and Chenonceau. The châteaux, numbering more than three hundred, represent a nation of builders starting with the necessary castle fortifications in the 10th century to the splendor of those built half a millennium later. When the French kings began constructing their huge châteaux here, the nobility, not wanting or even daring to be far from the seat of power, followed suit. Their presence in the lush, fertile valley began attracting the very best landscape designers and architects. The Loire Valley is an area steeped in history and because of its riches, one that has been fought over and influenced by a variety of adversaries from the Romans to Atila the Hun. The formation of the region as we know it today began after its conquest by Julius Caesar in 52 BC. It is however, Emperor Augustus who is credited with bringing peace and stability to the Loire Valley. This stability saw the growth of towns such as Orleans (Genabum), Tours (Caesarodunum), Le Mans (Noviodunum), Angers (Juliomagus), Bourges (Avaricum) and Chartres (Autricum). The Roman’s greatest influence however might be considered to be the introduction of the first grape vines to the region, as shown in the wine AOC map shown above.

During the later years of the elderly Charlemagne’s rule, the Vikings made advances along the northern and western perimeters of his kingdom. Viking advances were allowed to escalate, and their dreaded longboats were sailing up the Loire and Seine Rivers and other inland waterways, wreaking havoc and spreading terror. In 843, Viking invaders murdered the Bishop of Nantes, and a few years after that, they burned the Church of Saint Martin at Tours, and in 845 the Vikings sacked Paris. During the reign of Charles the Simple (898–922), Normans under Rollo were settled in an area on either side of the Seine River, downstream from Paris, that was to become Normandy. The area around the lower Seine, ceded to Scandinavian invaders as the Duchy of Normandy in 911, became a source of particular concern when Duke William took possession of the kingdom of England in the Norman Conquest of 1066, making himself and his heirs the King’s equal outside France (where he was still nominally subject to the Crown). In a separate post I have explored the history of Normandy.

Brittany was heavily attacked by the Vikings at the beginning of the 10th century. The kingdom lost its eastern territories, including Normandy and Anjou, and the county of Nantes was given to Fulk I of Anjou in 909. However, Nantes was seized by the Vikings in 914, and was eventually liberated by Alan II of Brittany in 937. Alan II totally expelled the Vikings from Brittany and recreated a strong Breton state. He paid homage to Louis IV of France and thus Brittany ceased to be a kingdom and became a duchy. Several Breton lords helped William the Conqueror to invade England and received large estates there. Some of these lords were very powerful and medieval Brittany was far from being a united nation. The foreign policy of the duchy changed many times; the dukes were usually independent but they often contracted alliances with England or France.

The line of Charlemagne died out in 987, and the nobles elected Hugh Capet, count of Paris, to the throne. Hugh’s authority, however, was severely limited. The Royal Domain was limited to a small area around Paris and Orléans. In the chaos of the 10th century the regional counts had become virtually independent princes within their own territories. For all their weakness, the position of the early French kings was recognised and sanctified by the Church, and in a religious age this gave them a prestige not enjoyed by any other prince or lord. This enabled Hugh and his successors to gradually build up their power within their kingdom.

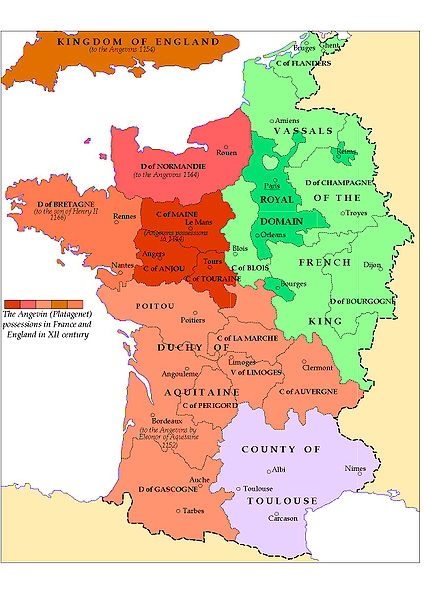

The Counts of Anjou had been vying for power in north-western France (western Loire Valley) for a long time. The Counts were recurrent enemies of the Dukes of Normandy and of the Dukes of Brittany and sometimes even of the King himself. Fulk III (972-1240) of Anjou commissioned many buildings, primarily for defensive purposes. While fighting against the Bretons and Blesevins, protecting his territory from Vendôme to Angers and from there to Montrichard, he had more than 100 castles, donjons (dungeons or central keep), and abbeys constructed, including those at Château-Gontier, Loches (a stone keep), and Montbazon. He built the donjon at Langeais (990), one of the first stone castles. They would later become the sites of many of the grand chateaux we see today. Chinon was to become the popular residence of the Plantagenet kings of England after they had gained the County of Anjou through marriage during the 11th century. Fulk IV claimed rule over Touraine, Maine and Nantes; however, of these only Touraine proved to be effectively ruled, as the construction of the castles of Chinon, Loches and Loudun exemplify. Tours in the central Loire valley was actually a larger city than Paris at this time with its growth centered around the followers of Saint Martin. Anjou to the west and Blois to the east had feuding, powerful nobles building fortresses to protect their territories. Fulk IV married his son Fulk V to Eremburga, the heiress of Maine, thus unifying it with Anjou. While the dynasty of the Angevins was successful, their rivals, the Normans, had conquered England, while the Poitevins had become Dukes of Aquitaine as well as Dukes of Gascony and the Count of Blois became Count of Champagne.

Geoffrey V (1113-1151), called the Handsome and Plantagenêt, was the Count of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine by inheritance from 1129 and then Duke of Normandy by conquest from 1144. Geoffrey was the elder son of Fulk V of Anjou and Eremburga de La Flèche, daughter of Elias I of Maine. By his marriage to the Empress Matilda, daughter and heiress of Henry I of England, Geoffrey had a son, Henry Curtmantle (Henry II), who succeeded to the English throne and founded the Plantagenêt dynasty to which Geoffrey gave his nickname. Geoffrey received his nickname from the yellow sprig of broom blossom (genêt is the French name for the planta genista, or broom shrub) he wore in his hat. In 1152, he married France’s newly-divorced ex-queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, who ruled much of southwest France. After defeating a revolt led by Eleanor and three of their four sons, Henry had Eleanor imprisoned, made the Duke of Brittany his vassal, and in effect ruled the western half of France (and the Loire Valley) as a greater power than the French throne.

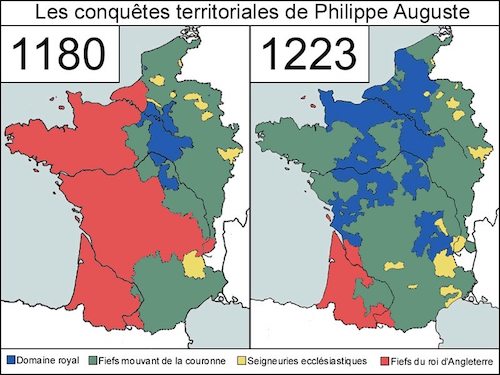

The reign of Philip II Augustus (junior king 1179–1180, senior king 1180–1223) marked an important step in the history of French monarchy. His reign saw the French royal domain and influence greatly expanded. He set the context for the rise of power to much more powerful monarchs like Saint Louis and Philip the Fair. Philip II was victorious at Bouvines thus annexing Normandy and Anjou into his royal domains. This battle involved a complex set of alliances from three important states, the Kingdoms of France and England and the Holy Roman Empire. Philip II spent an important part of his reign fighting the Angevin Empire, which was probably the greatest threat to the King of France since the rise of the Capetian dynasty. During the first part of his reign, Philip II tried using Henry II of England’s son against him. He allied himself with the Duke of Aquitaine and son of Henry II, Richard the Lionheart, and together they launched a decisive attack on Henry’s castle and home of Chinon and removed him from power. Richard replaced his father as King of England afterward. The two kings then went crusading during the Third Crusade; however, their alliance and friendship broke down during the Crusade. The two men were once again at odds and fought each other in France until Richard was on the verge of totally defeating Philip II. The crown of France was saved by Richard’s demise after a wound he received fighting his own vassals in Limousin (capital Limoges). John Lackland (King John), Richard’s successor, refused to come to the French court for a trial against the Lusignans and, as Louis VI had done often to his rebellious vassals, Philip II confiscated John’s possessions in France. John’s defeat was swift and his attempts to reconquer his French possession at the decisive Battle of Bouvines (1214) resulted in complete failure. Philip II had annexed Normandy and Anjou, plus capturing the Counts of Boulogne and Flanders, although Aquitaine and Gascony remained loyal to the Plantagenet King.

The next century saw a gradual consolidation of France and the Royal Domain, bringing in the counties of Toulouse and Langedoc, Provence, and Burgundy by marriage. Southern Flanders and Lyon were annexed into France in 1312 along with numerous smaller territories. The castle of Angers had been the seat of the Plantagenêt Court and the dynasty. The Angevin Empire disappeared in 1204-1205 when the King of France, Philip II, seized Normandy and Anjou. Henceforth a part of the Kingdom of France, Angers became the “Clé du Royaume” (Key to the Kingdom) facing independent Brittany. In 1228, during Louis IX’s minority, Blanche of Castile (the mother of Saint Louis) decided to fortify Angers and to rebuild the castle. It can still be seen today.

Another royal city was Chinon, especially during the reign of Henry II (Henry Plantagenêt, Count of Anjou, crowned King of England in 1154). The castle was rebuilt and extended, becoming one of his favorite residences. It was where court was frequently held during the Angevin Empire. The outcrop of rock on which the Royal Fortress of Chinon was built is a strategic site located at the meeting point of three French provinces: Anjou, Poitou and Touraine, on the banks of the Vienne river a little ways before it empties into the Loire. Chinon was included in the French Royal Domain in 1205 when Phillip II seized the Plantagenêt holdings. It was during the Hundred Years’ War that the town took on a new lease of life, as the heir apparent, the future Charles VII of France, had sought refuge in 1418 in the province. The town remained faithful to him and he made lengthy stays at his court in Chinon. In 1429, Joan of Arc came here to acknowledge him.

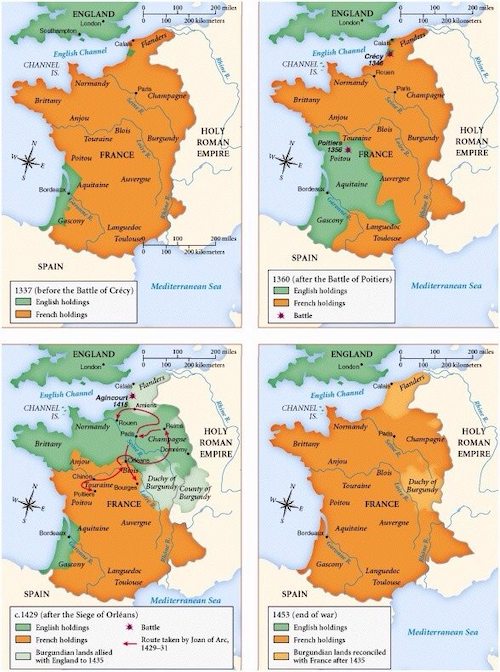

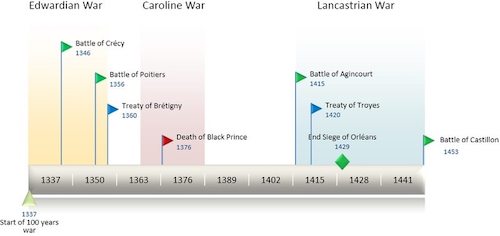

The Hundred Years’ War was a series of conflicts waged from 1337 to 1453 between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of France for control of the French throne. Many allies of both sides were also drawn into the conflict. The death of Charles IV in 1328 without male heirs ended the main Capetian line (from Hugh Capet). Under Salic law the crown could not pass through a woman (Philip IV’s daughter was Isabella, whose son was Edward III of England), so the throne passed to Philip VI, son of Charles of Valois. This, in addition to a long-standing dispute over the rights to Gascony in the south of France, and the relationship between England and the Flemish cloth towns, led to the Hundred Years’ War of 1337–1453. The actual reasons for the war were that the French did not want an English king and the English wanted their land in western France back. Edward III skillfully played on his claim to the French throne during the 1340s and 1350s to lure discontented French princes and provinces into alliance with him. Among these were the Flemish, always open to English pressure because of commercial links with England, the Montfort claimants to the duchy of Brittany in the succession war that broke out there in 1342, and Charles of Navarre, of the French blood royal and a great Norman vassal and landowner, in the 1350s. These alliances enabled Edward to render substantial regions of France virtually ungovernable from Paris, and to keep the fighting on French soil, going in between with occasional English large, swift expeditions called chevauchées.

The wars started out poorly for France when the English attacked Normandy, won the battle of Crecy in 1346, and captured Calais. In 1348-1350 the bubonic plague came to Europe killing about 1/2 the population of France and 1/3 of England. The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, killing an estimated 75 to 200 million people and peaking in Europe in the years 1348–50 CE. Philip VI died in 1350 (not from the plague) and his son, John II took up the war and was captured by the English at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356. The subsequent treaty of Brétigny terms in 1360 were that France should pay three million crowns for King John’s ransom, and that he would cede to Edward an enlarged Aquitaine, wholly independent of the French crown. In return, Edward would renounce his claim to the French throne. John II died in captivity and both Edward III and his son died in 1377 and 1376, respectively. In France Charles V, son of John II, discarded the treaty, recovered almost all the lost French territory, and established a standing army. Unfortunately, his successor Charles VI, crowned at age 11 in 1380, experienced bouts of psychosis in his twenties. The dukes of Burgundy and Orléans among others rushed in to fill the power vacuum. The Duke of Orléans, turned to his father-in-law Bernard VII, Count of Armagnac, for support against John the Fearless. This resulted in the Armagnac-Burgundian Civil War. Henry V saw an opportunity and in 1415 overwhelmingly defeated the pursuing French army at Agincourt in Picardy. The French battle casualties were horrific, and the royal dukes of Orléans and Bourbon were taken prisoner. After the fall of Rouen, the Norman capital, in January 1419, the English were able to bring the whole duchy under their control, and they took Paris and all of northern France. In 1420 Philip, the Duke of Burgundy, agreed to ally with the English and to broker an agreement with the ailing Charles VI of France whereby Henry V would marry Charles’s daughter Catherine, disown his son Charles VII, the dauphin, and recognize Henry V of England as his heir to the French throne. Henry V would then act as regent for Charles while he lived. These became the terms of the Treaty of Troyes of 1420.

These terms were widely accepted in northern France, but not in the south. When Henry V died in August 1422, followed by Charles VI in October, the nine-month-old Henry VI of England (son of Henry and Catherine) was recognized as king of France in Paris. But in the south, the Armagnacs upheld the succession of the dauphin, Charles VII. Orléans was attacked in September 1428, but the force was too small to attempt an immediate storming. The aim had to be to starve the garrison out. At first it looked as if there was little chance of a relief for the defenders, but in February 1429, Joan of Arc arrived at the dauphin’s court at Chinon with her story of the voices that had given her the mission of ridding France of the English. I have covered Joan of Arc in a separate post. With her assistance, the tide of war changed and Charles VIII was crowned King of France in Reims. After Joan’s capture in the following year and her subsequent execution for heresy, the English succeeded in recovering some of the towns they had lost in the wake of her victories and more or less held their own for a while. But in 1435, Philip, Duke of Burgundy, abandoned his English alliance at the Congress at Arras, and recognized Charles VII as his king. This dealt a mortal blow to English hopes of making the Troyes settlement stick. Paris was reconquered in 1436, Normandy in 1449-1450 and Gascony in 1451. Soon after, with Bordeaux once more in French hands, there was nothing left of the former English territories in France, except for Calais. The war was effectively over, even though it would not officially end for many years.

The Hundred Years’ War was a time of rapid military evolution. Weapons, tactics, army structure, and the social meaning of war all changed, partly in response to the war’s costs, partly through advancement in technology and partly through lessons that warfare taught. The war stimulated nationalistic sentiment. It devastated France as a land, but it also awakened French nationalism. The Hundred Years’ War accelerated the process of transforming France from a feudal monarchy to a centralized state. The conflict became one of not just English and French kings but one between the English and French peoples. There were constant rumors in England that the French meant to invade and destroy the English language. National feeling that emerged out of such rumors unified both France and England further. The Hundred Years’ War basically confirmed the fall of the French language in England, which had served as the language of the ruling classes and commerce there from the time of the Norman conquest until 1362.

The shock in England over the loss of its formerly wide overseas empire was very great. Popular rage against the counsellors and commanders deemed responsible had much to do with the outbreak in the mid-1450s of civil war (the “Wars of the Roses”). The recovery of the lost lands in France long remained a wishful national aspiration, but in material terms the consequences of their loss, for Englishmen living in England at least, was not very great. Probably the greatest outcome was the eventual joining of the houses of Lancaster and York into the house of Tudor, both lines of the Plantagenêt dynasty, by King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York in 1486. They thus reunited the two royal houses, merging the rival symbols of the red and white roses into the new emblem of the red and white Tudor Rose. Their son was the famous Henry VIII.

Château d’Amboise was built on a spur above the River Loire. Amboise and its castle descended through the family to Fulke III in 987. Expanded and improved over time, in 1434 it was seized by Charles VII of France, after its owner, Louis d’Amboise, was convicted of plotting against Louis XI and condemned to be executed in 1431. However, the king pardoned him but took his château at Amboise. Once in royal hands, the château became a favorite of French kings, from Louis XI to Francis I. Charles VIII decided to rebuild it extensively, beginning in 1492 at first in the French late Gothic Flamboyant style and then after 1495 employing two Italian mason-builders, Domenico da Cortona and Fra Giocondo, who provided at Amboise some of the first Renaissance decorative motifs seen in French architecture. The names of three French builders are preserved in the documents: Colin Biart, Guillaume Senault and Louis Armangeart. Following the Italian War of 1494–1495, Charles brought Italian architects and artisans to France to work on the château, and turn it into “the first Italianate palace in France”. King Francis I was raised at Amboise, which belonged to his mother, Louise of Savoy, and during the first few years of his reign the château reached the pinnacle of its glory. As a guest of the King, Leonardo da Vinci came to Château Amboise in December 1515 and lived and worked in the nearby Château Clos Lucé, connected to the château by an underground passage. Henry II and his wife, Catherine de’ Medici, raised their children in Château Amboise along with Mary Stuart, the child Queen of Scotland who had been promised in marriage to the future French Francis II.

Chambord is the largest château in the Loire Valley, it was built to serve as a hunting lodge for François I, who maintained his royal residences at Château de Blois and Château d’Amboise. The original design of the Château de Chambord is attributed, though with several doubts, to Domenico da Cortona. Some authors claim that the French Renaissance architect Philibert Delorme had a considerable role in the château’s design, and others have suggested that Leonardo da Vinci may have designed it. Chambord was altered considerably during the twenty-eight years of its construction (1519–1547) during which it was overseen on-site by Pierre Nepveu. With the château nearing completion, François showed off his enormous symbol of wealth and power by hosting his old archnemesis, Emperor Charles V at Chambord.

The Château de Blois has 564 rooms and 75 staircases although only 23 were used frequently. There is a fireplace in each room. There are 100 bedrooms. It became the favorite royal residence and the political capital of the kingdom under Charles’ VIII son, King Louis XII. At the beginning of the 16th century, the king initiated a reconstruction of the main block of the entry and the creation of an Italian garden in terraced parterres that occupied the present Place Victor Hugo and the site of the railway station. When Francis I took power in 1515, his wife Queen Claude had him refurbish Blois with the intention of moving to it from the Château d’Amboise. Francis I initiated the construction of a new wing and created one of the period’s most important libraries in the castle. But, after the death of his wife in 1524, he spent very little time at Blois and the massive library was moved to the royal Château de Fontainebleau where it was used to form the royal library that forms the core now of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The last of the royal castles in the Loire Valley was Chenonceau. Catherine de Medici was the mother to the last three kings of the Valois line and the wife of King Henry II. When Henry died after a jousting accident, Catherine ejected Diane de Poitiers, the king’s mistress, from Chenanceau and spent the rest of her life raising and protecting her children from this château. The French Wars of Religion dominated the rules of her three sons, Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III. On one side were the Catholics and later the Catholic League led by the Dukes of Guise and on the other, the Calvinist Huguenots with a considerable following among the nobility. Francis II ruled for only a year from 1559 to his death at 16 in 1560. The ten-year-old Charles IX was immediately proclaimed king and the government was dominated by his mother, Catherine de’ Medici, who at first acted as regent for her young son. Queen Catherine, though nominally a Catholic, tried to steer a middle course between the two factions, attempting to keep (or restore) the peace and augment royal power. The wars continued and after the military leaders of both sides were either killed or captured in battles at Rouen, Dreux, and Orléans, the regent mediated a truce and issued the Edict of Amboise (1563). The privileges granted to Protestants were widely opposed, however, leading to their cancellation and the resumption of war, in which the Dutch Republic, England, and Navarre intervened on the Protestant side, while Spain, Tuscany and Pope Pius V supported the Catholics. As a peace settlement, a marriage was arranged between Charles’ sister Margaret of Valois and Henry of Navarre, the future King Henry IV, who was at that time heir to the throne of Navarre and one of the leading Huguenots, to be held in Paris. Four days after the wedding, on August 24, 1572, Paris erupted into the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre, a systematic slaughter of Huguenots that was to last five days in Paris and throughout France, killing over 10,000 Hugenots. Charles IX died two years later at the age of 23 in 1574 from tuberculosis.

Henry III was born at the Royal Château de Fontainebleau, Seine-et-Marne, the fourth son of King Henry II and Catherine de’ Medici and grandson of Francis I of France and Claude of France. He was his mother’s favorite, she called him chers yeux (“Precious Eyes”) and lavished fondness and affection upon him for most of his life. As the fourth son of King Henry II of France and Catherine de’ Medici, Henry was not expected to assume the throne of France. He was thus a good candidate for the vacant Polish-Lithuanian throne, and he was elected with the dual titles King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. Of his three older brothers, two would live long enough to become king, but both died young and without a legitimate male heir. He abandoned Poland upon receiving word that he had inherited the throne of France at age 22. Henry was crowned king of France on 13 February 1575 at Reims Cathedral. In 1576, Henry signed the Edict of Beaulieu, which granted many concessions to the Huguenots. His action resulted in the Catholic activist Henry I, Duke of Guise, forming the Catholic League. After much posturing and negotiations, Henry was forced to rescind most of the concessions that had been made to the Protestants in the edict.

In 1584, the King’s youngest brother and heir presumptive, Francis, Duke of Anjou, died. Under Salic Law, the next heir to the throne was Protestant Henry of Navarre, a descendant of St. Louis IX in the Bourbon line. On May 12, 1588, when the Duke of Guise entered Paris, an apparently spontaneous Day of the Barricades erupted in favor of the Catholic champion. Henry III fled the city to Château de Blois leaving the Duke of Guise in control of Paris. In December 1588, Henry III had Henry I of Guise murdered, along with his brother, Louis Cardinal de Guise. The Parliament instituted criminal charges against the king, and he was compelled to join forces with his heir, the Protestant Henry of Navarre, by setting up the Parliament of Tours. On August 1, 1589, Henry III lodged with his army at Saint-Cloud, Hauts-de-Seine, and was preparing to attack Paris, when a young fanatical Dominican friar, Jacques Clément, carrying false papers, was granted access to the king and killed him. Henry of Navarre went on to become King Henry IV of France, the first of the Bourbon Dynasty, after converting to Catholicism and ending the 30 year war of Religion.

The French kings retreated back to Paris and their grand Châteaux became glorious relics of a bygone age. Even after Louis XIV built Versailles, the nobility and the wealthy bourgeoisie continued to renovate existing châteaux or build lavish new ones as their summer residences in the Loire. The 17th and 18th centuries saw the re-establishment of the Catholic Church. This resulted in an increase in the number of convents and seminaries and a decline in the Protestant movement within the Loire Valley. The French Revolution saw a number of the great French châteaux destroyed and many ransacked, their treasures stolen. The overnight impoverishment of many of the deposed nobility, usually after one of its members lost their head to the guillotine, saw many châteaux demolished.

I will end here, this might have been shorter but without the details it would be hard to understand the strategic importance of the Loire Valley, its Dukes, Duchies, intrigues, wars and in fact the reasons these castles and chateaux were built. In a very real sense, the history of the Loire valley is the history of medieval France.

References:

Normandy and William the Conquerer: /rouen-and-normandy/

TimeMaps: http://www.timemaps.com/history/france-200ad/

Anjou, Maine and Touraine: http://www.rome.webz.cz/Anjou.htm

Experience Loire: http://www.experienceloire.com/history%20of%20the%20Loire%20Valley.htm

Wikipedia Royal Domain: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crown_lands_of_France

BBC Hundred Years War: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/middle_ages/hundred_years_war_01.shtml

Joan of Arc: /joan-darc/