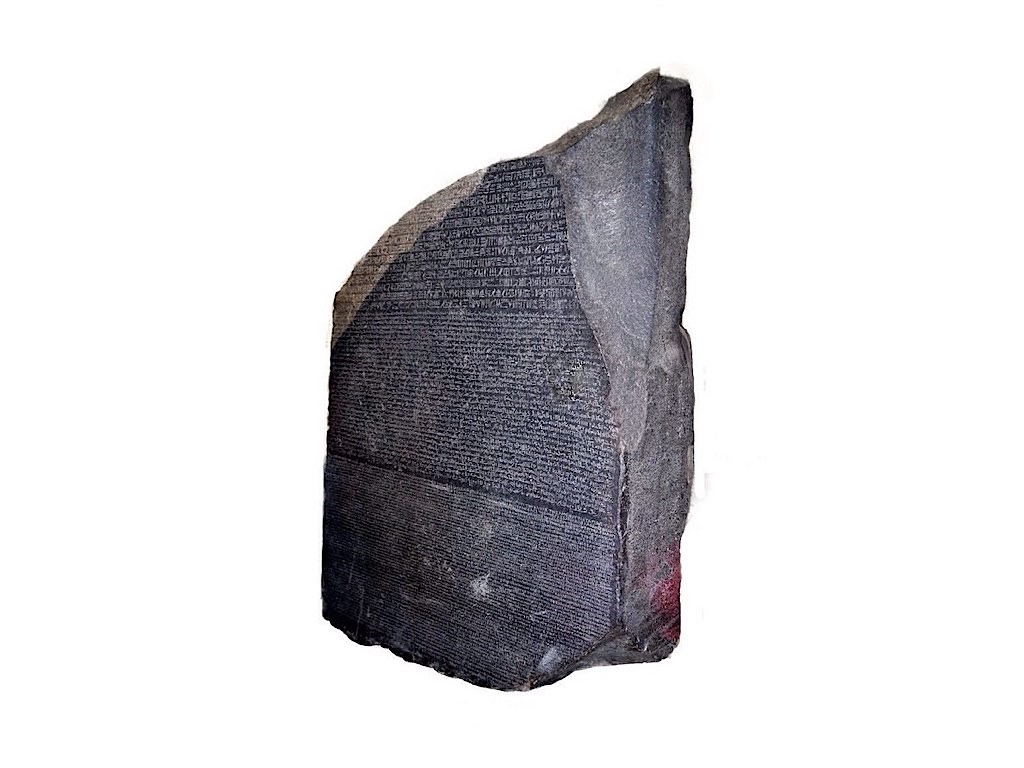

The Rosetta Stone is a very famous historical artifact, almost everyone has heard of it and most people know it has something to do with language. It is a black basalt slab that provided scholars with their first key to ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing. Prior to this point Egyptian hieroglyphics were considered to be a pictorial form of writing without a real grammar and the Egyptians were considered by the English to be a backward people. Using the Rosetta Stone as a dictionary, scholars were able to translate other inscriptions and manuscripts written in hieroglyphics opening up three thousand years of remarkable Egyptian history. The stone was discovered in 1799 near el-Rashid, known as Rosetta in Egypt, by a French engineer of Napoleon’s army, Captain François-Xavier Bouchard, built into the wall of an ancient Arab fort (Fort St Julien) which he’d been assigned to tear down.

The ill-fated French expeditionary force that occupied Egypt under Napoleon’s command from July 1798 until 1801 (see my post) included over 100 of France’s leading scientists. While in Egypt, the scientists recorded investigations on natural history, archaeology, physical geography, technology, weights and measures, hydrography, meteorology, chemistry, medicine, and other aspects of Egyptian culture and environment. The great monuments were examined and the science of Egyptology was founded. One of the most important discoveries in that field was the Rosetta Stone. Their work was published on returning to France as the “Description de l’Égypte“, in many volumes of truly monumental dimensions, with beautiful engraved plates. The Rosetta Stone came to London and to the British Museum (where it remains) in 1802, after the French surrender to the British forces in Egypt in 1801.

The stone fragment carried three parallel inscriptions. One, in Greek, identified the passage as a decree issued by Ptolemy V in 196 B.C. The other two, written in Egyptian hieroglyphics and demotic (simplified hieroglyphic) scripts, both indecipherable at the time, appeared from their nearly equal lengths to represent translated versions of the Greek text. The Greek text was fairly easy to read, if a little boring. It is a decree prepared in 196 B.C. by a group of priests ordering the commemoration of the first anniversary of the coronation of their pharaoh, Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The priests praised the pharaoh for many laudable deeds, such as canceling overdue taxes and granting amnesty to prisoners. In closing, the decree directed that it be inscribed in hieroglyphic, demotic, and Greek on stone slabs. The stele is a late example of a class of donation stelae, which depicts the reigning monarch granting a tax exemption to the resident priesthood. Pharaohs had erected these stelae over the previous 2,000 years, the earliest examples dating from the Egyptian Old Kingdom.

In 332 BC, Egypt was conquered by Alexander the Great. After Alexander’s death, his former general Ptolemy I ruled Egypt. His Greek descendents known as the Ptolemies ruled Egypt for the next 300 years. The Ptolemaic period witnessed a fusion of Greek and Egyptian cultures. Greek was the official language of the court, while hieroglyphs were limited to use by the priests. Demotic Egyptian was the native script used for everyday purposes that evolved from Hieroglyphs dating from about 643 B.C. Hieroglyphic writing died out in Egypt in the fourth century AD. Monumental use of hieroglyphs ceased after the closing of all non-Christian temples in the year 391 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I.

The ancient scripts were replaced with ‘Coptic’, a script consisting of 24 letters from the Greek alphabet supplemented by six demotic characters used for Egyptian sounds not expressed in Greek. The ancient Egyptian language continued to be spoken, and evolved into what became known as the Coptic language, but in due course both the Coptic language and script were displaced by the spread of Arabic in the 11th century. The final linguistic link to Egypt’s ancient kingdoms was then broken, and the knowledge needed to read the history of the pharaohs was lost. This understanding of the continuity of the language culture of Egypt through millennia was the correct hypotheses of Jean-François Champollion. By 1821, he had come to the conclusion that that “the hieratic (demotic) “is nothing but a simplification of hieroglyphic,” and that it “should be considered as shorthand for the hieroglyphs.” Interestingly, in 2012, the University of Chicago just finished a 40 years project to update and supplement a more modest glossary of Demotic words published in German in 1954 by Wolja Erichsen, a Danish scholar. It is called the Chicago Demotic Dictionary, available online.

The discovery of the Stone was not made public until September 1799, in an article printed in the Courrier de l’Egypte. It was shipped to Cairo in mid-August, and became an object of study at the Institute. Jean-Joseph Marcel and Remi Raige were able to identify the unknown cursive script, Demotic, but they were unable to read it. Copies of the scripts were made by the lithographers Marcel and A. Galland, who covered the Stone’s surface with printer’s ink, layed sheets of paper over it and used rollers to obtain an impression. Several sheets were sent to scholars throughout Europe, and two copies were presented to citizen Du Theil of the Institute Nationale de Paris by General Charles-François-Joseph Dugua (former Commandant of Cairo) on his return from Egypt. A French translation of the text was made by Du Theil, revealing that the Stone “was a monument to the gratitude of some priests of Alexandria, or some neighboring place, towards Ptolemy Epiphanes.”

The hieroglyphs proved most difficult to read, because of the false assumption that hieroglyphs were only symbols for words and did not represent sounds. Georges Zoega had deduced in the 18th century, that proper names could be isolated, because they were contained in cartouches, or oval-shaped enclosures. An English scholar, Thomas Young, made some progress in identifying some of the proper names, such as Ptolemy, in the demotic and hieroglyphic texts in 1819. Young called his achievements “the amusement of a few leisure hours.” He lost interest in hieroglyphics, and brought his work to a conclusion by summarizing it in an article for the 1819 supplement to the Encyclopaedia Britannica. In 1822 a French scholar, Jean-Francois Champollion, drawing upon his knowledge of the ancient Coptic language of Egypt, correctly determined that the hieroglyphs represented both sounds and words, thus finding the key to the translation of hieroglyphics.

Champollion’s work on deciphering hieroglyphics was a life-long occupation. Ptolemy was the only name on the Rosetta Stone. Champollion, in 1822, saw copies of the brief hieroglyphic and Greek inscriptions of the Philae Obelisk, on which William John Bankes had tentatively noted the names “Ptolemaios” and “Kleopatra” (????????? in Greek) in both languages. The obelisk was said to have been fixed in a socket, bearing a Greek inscription containing a petition of the priests of Isis at Philae, addressed to Ptolemy, to Cleopatra his sister, and to Cleopatra his wife. There were several corresponding letters, indicated in green above (P, O, L and E). Also there were two letters or sounds indicated as the same, the letter “A”, indicated by the yellow arrow. The letter “T”, indicated by the red arrow, is not the same being represented by a half circle above and an outstretched hand below. Here, he assumed that this must also represent T, and assumed the notion of homophones: that more than one symbol or character could be used to express the same sound (as in English “phonetic” and “fancy”). He went on to decipher reproductions in the third volume of the “Description de l’Égypte”, which showed inscriptions of other Greek and Roman leaders. Finally he tackled the cartouche of Ramses which he finally solved.

The complete elaboration of Champollion’s discovery came in his 1824 masterpiece, the “Précis du Système Hieroglyphiques des Anciens Egyptiens”. As he stated at the outset, he would show that the alphabet he had established, applied to “all epochs,” and that his discovery of the phonetical values unlocked the entire system.

The Egyptian language was made up of sounds. Partly of vowels and consonants, however; hieroglyphs constantly ignored and left out vowels. How a word sounds in hieroglyphics is more important than how it is spelled. Hieroglyphs are also pictures. These signs had no order to how they were written. They could be written from left to right, right to left, or reading downwards, vertically. In viewing the pictures to decide which way it is read, look at the faces of men or animals. If the face is facing left, then the inscriptions is read from left to right. If the faces are facing right, then it is read right to left. In addition the symbols were crammed into the cartouche with no particular attention to the size of the consonant. The system of writing (and reading) hieroglyphs was intensely complex and very labor intensive. Reading hieroglyphics reminds me a lot of the game “Pictionary” but in Coptic. I am going to stop here, if you are really interested, please visit the links below.

References:

There is an Ipad App: Egyptian Hieroglyphs which I used to make the figures

How Champollion Deciphered the Rosetta Stone: http://www.schillerinstitute.org/fid_97-01/993_champollion.html

Napoleon and the Scientific Expedition to Egypt: http://www.lindahall.org/events_exhib/exhibit/exhibits/napoleon/index.shtml

Hieroglyph Typewriter: http://www.eyelid.co.uk/hieroglyphic-typewriter.html

Egyptian Stone Technology: http://www.theglobaleducationproject.org/egypt/articles/stonetech.php

Description de l’Égypte: http://www.wdl.org/en/item/80/

BBC: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians/decipherment_01.shtml

Sacred Texts: http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/trs/trs05.htm

Chicago Demotic Dictionary: https://oi.uchicago.edu/research/projects/dem/

Ancient Egypt History: http://www.ancient-egypt-history.com/2010/04/lesson-1.html#.UIWT7pG9KK0

Précis du Système Hieroglyphiques des Anciens Egyptiens (in French): http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hwtqcj;skin=mobile#page/n5/mode/1up